Säter mental hospital

September 17, 2020 20 min read

May 2022 update: Since I visited the mental hospital in December 2019, the town of Säter has acquired Fasta paviljongen. The plan is to demolish the building and build flats on the property. This should have happened during 2021, but the building is still standing. Preparations for the teardown started last year, but seem to have come to a halt. The trees around the building have been removed. Go to Säter during 2022 if you want to see the pavilion before it is turned into dust.

On a beautiful winter day in December 2019, I visited Säter; a small town in the county of Dalarna in central Sweden.

Säter has become synonymous with the psychiatric institution in Skönvik, an area on the outskirts of the town. Since it opened over 100 years ago, the institution has treated patients suffering from mental illnesses. While many of them could return to a normal life, others lived the rest of their lives at the mental hospital.

The hospital has earned quite a reputation because of its clinic for forensic psychiatry. Several of the most high profile Swedish criminals received treatment at the clinic over the years.

The hospital complex from the inauguration year of 1912 has little in common with today’s modern facility. Only four of the original 37 hospital buildings remain. Two of the old buildings are interesting for visitors.

Mentalvårdsmuseet is a mental health care museum housed in one of the old patient wards. The museum tells the story of how patients and staff lived and worked at Säter during the 20th century. The collections give an insight into how treatment of mental illnesses changed as new methods and drugs became available.

Fasta paviljongen was the original closed ward for forensic psychiatry at Säter. A new clinic replaced the old one in 1989, and the building was abandoned. Since then, Fasta paviljongen has become one of the primary spots for Swedish urban explorers.

It’s not allowed to enter the building, but judging by the amount of photos of the building’s decaying interiors available online, the prohibition doesn’t stop people interested in getting a glimpse of the hospital’s hidden history.

"Urban exploration, often shortened as UE or urbex, is the exploration of manmade structures, usually abandoned ruins or hidden components of the manmade environment."

It was an inspiring day exploring the museum, Fasta paviljongen and the old hospital cemetery. A lot of the historic background information in this post comes from the museum exhibitions and website.

The industrialization and rapid urbanization in the 19th century brought on fundamental changes to the living conditions of the citizens. An increasing number of patients were diagnosed with mental disorders. The authorities moved individuals deviating from the social norms off the streets and into the care of mental institutions.

In the early 20th century, the Swedish state made huge investments in new mental hospitals. The problem was that the early treatment methods didn’t cure the patients; they remained hospitalized for years. With a steady stream of new patients, the mental hospitals filled up.

The state continued to build new facilities and at the end of the 1960s, Sweden had 36,000 hospital beds for closed psychiatric care. With a population of only 8 millions, this was an unofficial world record.

"The term psychiatry was first coined by the German physician Johann Christian Reil in 1808 and literally means the medical treatment of the soul."

A firm belief in the healing power of nature influenced the decision to build mental hospitals in the idyllic countryside. The institutions were self-sustaining communities with their own farmlands for growing crops and keeping livestock.

The trend in mental health care was a humanistic treatment approach with fewer methods of coercion. To divide the patients into manageable groups, they were classified according to their anxiety levels. Patients with different classifications should not interact with each other. Clear rules and a strict day schedule should bring structure to the chaotic inner state of the patients.

To facilitate treatments according to these ideas, the mental hospitals were complexes of freestanding buildings called pavilions. A pavilion contained one patient ward and proper distances between the pavilions assured separation of patient groups.

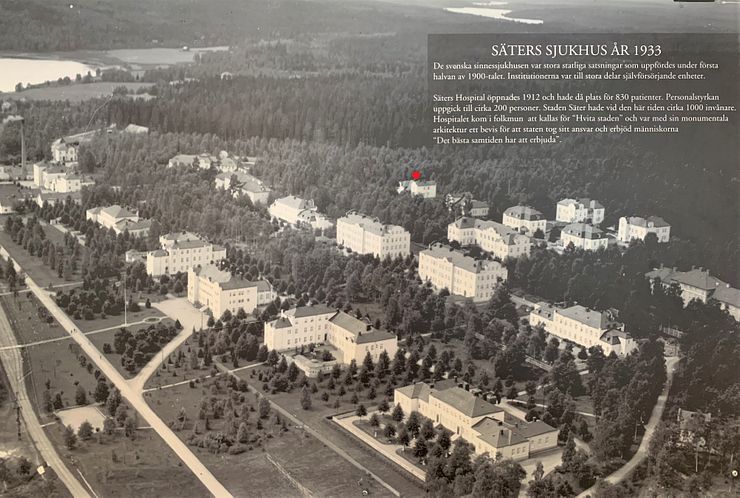

When the Säter mental hospital opened in 1912, it was one of the largest facilities in Sweden with 830 hospital beds. As a comparison, the town of Säter had 1000 inhabitants. The complex comprised 37 buildings of which 20 contained patient wards.

The hospital owned farmlands, forest and had its own railway. A central kitchen and bakery prepared all food on-site. The hospital church cared for the spiritual wellness of the patients and arranged funerals at a private cemetery.

An aerial photo from 1933 on display in the museum shows the scale of the hospital, it’s an impressing complex. The red dot marks the museum building.

Psychiatric theories and treatment methods were in constant evolution during the first half of the 20th century. The hospital buildings had to change accordingly to meet new requirements.

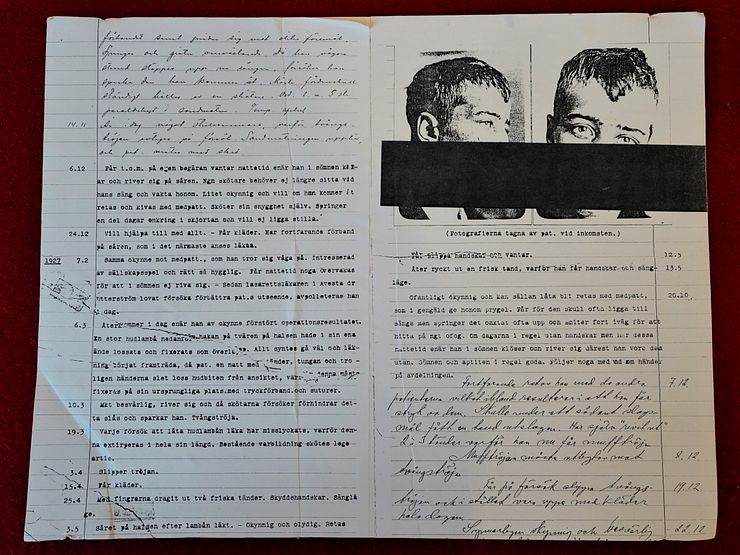

In the 1920s, the hospital added several new pavilions for very anxious patients. The rooms had beds bolted to the floor, hatched windows and tubs for long calming hydrotherapy treatments. The staff used straitjackets and restraint gloves on patients suffering from anxiety attacks or compulsive behavior.

Antipsychotic drugs didn’t exist, the only pharmacological tools available were sedatives (barbiturates) reducing the anxiety of psychotic patients. The drugs were addictive and could cause severe side effects.

Before the buildings were painted yellow, the Säter Hospital was known as the white city. The white stone buildings contrasted to the red wooden houses of the town of Säter.

The capacity at Säter continued to increase until the 1950s. At the peak in 1956, 1276 patients were admitted into the hospital. The upward trend turned when ideas about a more active care instead of institutionalizing patients in closed care gain ground.

Modern psychotropic drugs introduced in the 1950s revolutionized treatment of psychotic disorders. At Säter, anxious patients treated with psychotropics calm down and can take part in rehabilitating activities such as therapy and excursions outside the hospital grounds. The number of furloughed and discharged patients increases. Treatment times decrease from years or decades to less than a month in some cases.

A drug affecting behavior, emotions, thoughts, or perception. Psychotropics can be legal prescription medication or illicit drugs. Legal psychotropics are classified as anxiolytics (anti-anxiety), antidepressants, antipsychotics, mood stabilizers and stimulants.

This was a significant improvement, but the drugs didn’t help all patients. For some it was just a switch from a physical straitjacket to a mental one. High doses caused unexpected side effects, and patients suffered from loss of initiative and motivation.

The architects designed the hospital buildings to withstand the test of time, but they couldn’t foresee the coming changes in mental health care. After a few decades, some buildings were outdated and unsuitable for new types of treatment. Reconstructions of existing buildings and additions of new ones occur regularly from the 1960s and onwards. In the 1970s, the original main building is demolished and replaced.

The Swedish psychiatry continues its transformation towards outpatient care instead of institutional care. Suggestions to close the mental hospitals surface in the 1960s, but it takes until the 1980s before the psychiatric care is reorganized into smaller units with a different focus. The mental hospitals shut down and the patients are moved from the institutions and integrated into society.

In 1989, the new clinic for forensic psychiatry replaces the old ward, Fasta paviljongen. This marks the end of an era at Säter. The transition to the modern world completes with the closure of the last building from the hospital opening in 1912.

Much of the mystique surrounding Säter during the last century relates to Fasta paviljongen, the high-security closed ward. For almost 80 years, the ward was used for treatment of dangerous and very difficult patients. Mentally ill criminals from all parts of Sweden were admitted to the ward.

The pavilion looks like a prison with thick walls, barred windows, security systems and a yard surrounded by high concrete walls. The initial capacity was 27 patients, and the ward had many rooms for isolation. One can only imagine how life was inside the walls, especially in the early days before the use of modern antipsychotic medications.

The Swedish term fast paviljong originates from the German festes haus meaning fortified house.

After the closure of the ward in 1989, the building became a primary spot for Swedish urban explorers. The pavilion still stands, more than 30 years since it was abandoned, but time has taken its toll. The building is vandalized, and the interior covered in graffiti. A fire in 2002 destroyed a part of the roof and since then it’s forbidden to enter the building due to the risk of collapse.

Entering the building is punishable with a fine, but people are still doing it. Going inside the building is nothing I would recommend, but you can get a glimpse of how it looks inside by peeking through the broken windows.

For those of you who want to enter the building, I saw at least two ways to do it. I will not share my observations in the post, but if you want to know more, write me a message using the Contact page.

The building is in pretty bad shape after the fire, and the question is how long it will survive the threat of demolition? If you are interested in seeing this fascinating historic building, it’s a good idea to visit soon, or it might be gone when you arrive.

Fasta paviljongen is about 200m down the road from the museum (coordinates: 60.34087, 15.71185). It’s easy to locate the pavilion in the hospital grounds as it stands out from the rest of the buildings. The front of the building faces the road and at the back side is a high-walled yard. To reach the back side, it’s easiest to walk along the wall on the right side of the building.

With its crumbling facade and barred windows, the building looks sinister. The double door entrance is since long blocked by bricks to prevent people from entering the building.

As in most abandoned buildings, the interior is trashed, and the walls covered in graffiti. Some parts, like the intense ’70s style wallpaper in the room below, have survived the vandalization. How about an entire room with that wallpaper? I don’t think it had a calming effect on the patients!

A surprisingly large number of doors still hang on their hinges, but the torn down ones make good photo subjects.

The building has two main floors, an attic and a basement. Take extra care if you go up to the attic. It can be risky since the roof caved in during the fire in 2002. Going down to the basement is … dark, bring a flashlight.

While most of the furniture and equipment used in the ward are gone or destroyed, there are still plenty of interesting details to discover and take photos of.

Nature has taken over the yard where the patients got their daily dose of fresh air. It’s almost like entering a small forest of fir trees when stepping out on the yard through the open doorway at the back of the building.

For some weird reason, they put a barred window in the wall surrounding the yard. Why build a thick wall at a high security facility and put a weak spot in it?

There are things hidden among the trees, for example, a wooden gazebo where the patients could get shade from the sun. More recent additions are a bath tub and a ladder leaning against the wall. I bet the inmates would have made use of that ladder had it been there back in the days.

Looking out through the front facing windows, you see the modern hospital buildings. The rusty steel bars are cold to touch in the winter. Freedom, so close but yet so far.

If you go inside the closed ward, don’t miss going up to the second floor, where the most interesting rooms are.

A kitchen is maybe not what you expect to find in a prison-like closed ward at a mental hospital, but yet here it is. I don’t think anyone prepared food here as it was delivered from the central kitchen, but maybe the patients had their meals here?

The long corridors running through the length of the pavilion are spooky. Every step you take on the rubble covered floor makes a seemingly loud sound in the silent building. Imagine being here on a dark night, suddenly hearing footsteps somewhere in the building. Remember, if there isn’t an easy way into the ward, there is no easy way out either…

If you don’t feel like going into the building, you can do what I did and look through the lower windows. That will at least give you a feeling for how the abandoned pavilion looks today.

Mentalvårdsmuseet, the mental health care museum at Säter, opened in 1987. Preparations started already in 1983 with work on the museum building. The pavilion, Ward 21A from the old hospital complex, was restored to its original state from 1912.

The museum website and most of the information in the exhibitions are in Swedish, but they can arrange guided tours in English on request (book well in advance).

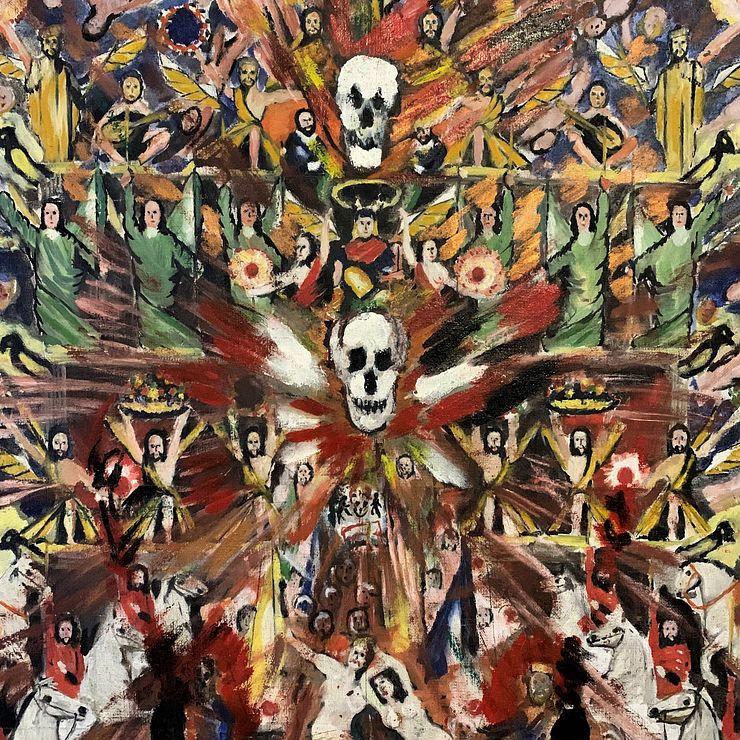

Even if you cannot understand all the information, it’s interesting to walk through the museum to see reconstructed interiors from the mental hospital, patient art and medical equipment on display.

The museum has limited opening hours, especially during the winter. During the low season, the opening hours are irregular and subject to change. Check the website for current information before going to Säter.

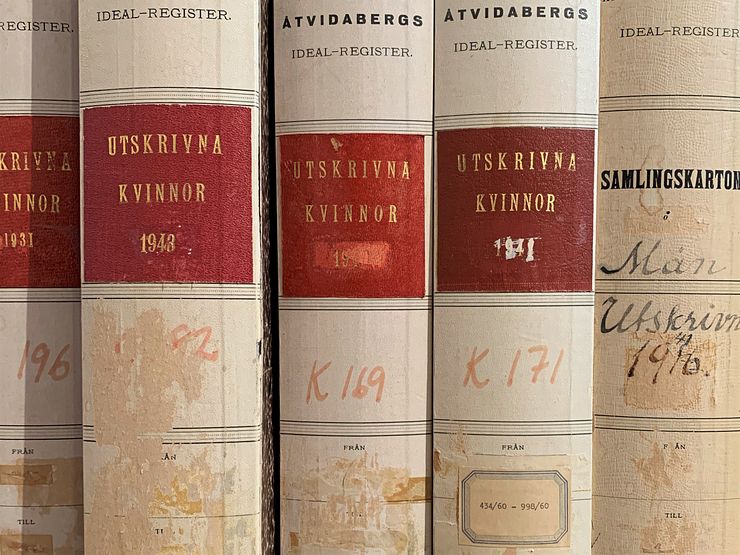

Foresighted staff members at the hospital started preserving objects for the museum collections in the 1950s. They realized that the mental health care system was about to change, and they wanted to save interesting objects for the future.

I visited the museum on Advent Sunday, when they had a special event with free entrance. Parking is available just outside the museum building. This is not a big tourist attraction, so you can expect a calm and stressless visit at the museum.

Most people don’t come in close contact with mental illness. It’s something that you read about or see depicted as movie clichés. The museum tells about real people with real problems they struggled with all their lives. It’s a reminder of how difficult it was to be mentally ill in a time without proper treatments. The patients suffered doubly, both from their illnesses and from insufficient treatment methods.

One of the three rooms at the museum contains a reconstructed patient dorm room. The photos on the wall are from early patient journals.

An excerpt from one journal tells that the patient has wounds after scratching himself while sleeping. He is hard to control and has to wear a straitjacket after tearing out two healthy teeth using only his fingers.

The staff lived at the premises, and there was a strict hierarchy for housing. Lower ranked staff lived in small rooms on top of the patient wards, while the chief physician enjoyed a spacious villa. A bus transported the staff into Säter and to the nearby town of Hedemora that had a liquor store.

One section in the museum shows surgical tools and other equipment used for different procedures and treatments. It inspired me to go home and read more about the methods. It was an interesting, but rather disturbing read.

The eugenic movement grew strong in Europe and North America in the early 20th century. Today it’s hard to understand, but many civilized countries adopted eugenic policies and implemented sterilization programs targeting persons deemed unfit to reproduce.

The practice or advocacy of controlled selective breeding of human populations (as by sterilization) to improve the population's genetic composition.

— Merriam-Webster

The parliament approved the first Swedish sterilization law in 1934 and strengthened it in 1941. The state had the power to enforce compulsory sterilization of people with heritable diseases. Suffering from a severe mental illness, being feebleminded or living an antisocial lifestyle could also cause a person to be judged unsuitable to foster a child.

Between 1935 — 1975, 63,000 persons were sterilized in Sweden and of these, 90% were women. The sterilization law was abolished in 1976, and in 1999 the parliament adopted a new law giving persons coerced into sterilization the right to monetary compensation.

Of all the horrible treatment methods used on mental patients, I think lobotomy is the worst of them all. The procedure, also called leucotomy, cuts the connections between the frontal lobes and the rest of the brain.

It’s a kind of psychosurgery which became widely used in the 1940s. The Portuguese neurologist, António Egas Moniz, received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1949 for “discovery of the therapeutic value of leucotomy in certain psychoses”.

Surgical severance of nerve fibers connecting the frontal lobes to the thalamus that has been performed to treat mental illness.

— Merriam-Webster

All this sounds very scientific and advanced, but with today’s knowledge, the procedure appears barbaric. Leucotomy was a quick operation where the surgeon drilled a hole in the skull, pushed a steel spike (leucotome) into the brain and moved it from side to side.

For someone like me, that’s not a brain surgeon, lobotomy doesn’t seem that different from drilling holes in the skull to release evil spirits. I know that the surgeons lobotomized patients because they thought the alternative was worse, but they didn’t do proper follow-ups of the effects. People suffered from severe side effects like reduced intellect and personality changes.

The winds turned in the 1950s when several countries banned the procedure. Studies showed the poor results of lobotomy. The first generation of effective psychiatric drugs also contributed to the downfall in popularity of psychosurgery.

Many psychiatric institutions used hydrotherapy with both warm and cold water. Warm baths, lasting from hours to several days, calmed agitated patients.

I learned something new at the museum. I had never heard about insulin coma therapy. It was the Austrian psychiatrist Manfred Sakel who started experimenting with the method in 1927. Säter started treatments in 1941, and it was used extensively for schizophrenic patients during the 1940s and 1950s.

The patient was injected with a substantial dose of insulin to produce a coma. After 30—40 minutes, the coma was ended by applying glucose via a stomach tube. A full treatment comprised 50—60 comas administered six days a week. That’s about two months that the patient had to endure this procedure!

Another, more well-known treatment, was electroshock therapy. It is still in use today, but the name changed to electroconvulsive therapy. The idea is to induce seizures in the patient by sending electricity through the brain. The method was, together with insulin coma therapy, the most common treatment at Säter during the 1940s and 1950s.

The mental hospital had its own chapel and cemetery. Some 200 persons attended the first burial in 1913 and the hospital orchestra played the funeral music. This was in stark contrast to most of the simple patient funerals with no relatives present.

About 800 patients are buried at the cemetery, many more than the number of white crosses marking the graves. The last funeral was held in 1951.

Säter is about 200km (124 miles) northwest of Stockholm, and the easiest way to visit is by car. I did it as a long day trip from Stockholm, a one-way drive of 2h15m.

You can also take the train to Säter, check the timetable and buy tickets at SJ. The fastest train from Stockholm Central to the train station in Säter takes about 2h.

It’s a 3km walk from the station in the town center to the hospital area in Skönvik. There are also local buses to Skönvik operated by Dalatrafik. You can return to Stockholm with a train later the same day if you are not planning to spend more time in beautiful Dalarna.

Here are the map coordinates for the interesting locations in Skönvik.

The museum and Fasta paviljongen are close to each other. After visiting them, you can drive or walk to the cemetery about 1km further along the road through Skönvik (follow Vedgårdsvägen and then Jönshyttevägen). You will pass the clubhouse of the local golf club. It’s limited parking space near the cemetery so if you drive you can also park at the golf club.

Comments

Comments are closed. Contact me if you have a question concerning the content of this page.