Wolfsschanze - Wolf's Lair

December 17, 2020 20 min read

During World War II, Adolf Hitler and his entourage moved between headquarters located throughout occupied Europe. Hitler had at least fourteen Führerhauptquartier, military command centers with living quarters, at his disposal.

The most well-known headquarters was the Führerbunker in Berlin, where Hitler committed suicide in 1945. He ended his life in Berlin, but Hitler spent little time in the capital during the war. World War II lasted for six years, and Hitler spent about a third of that time in Wolfsschanze, a base in northeastern Poland.

Wolfsschanze is German for Wolf’s Lair, and it was here that Claus von Stauffenberg tried to assassinate Hitler with a bomb in July 1944. The assassination attempt was the culmination of a conspiracy master plan to overthrow the Nazi regime.

Hitler survived with minor injuries and continued his reign of terror for another nine months.

The retreating Germans destroyed and abandoned the base before Soviet forces arrived at Wolfsschanze in January 1945. Patinated by time, the bunker ruins are still hiding in the forest today. The historical Wolfsschanze site sees over 300.000 visitors each year.

In June 1941, Hitler opened up the Eastern Front by putting Operation Barbarossa in motion. The goal was to conquer and occupy the western Soviet Union and repopulate the territory with Germans. To oversee the campaign, the German High Command needed a military headquarters on the Eastern Front.

Organisation Todt, the civil and military engineering organization in Nazi Germany, built the headquarters in the forest outside the town of Rastenburg in East Prussia.

Rastenburg is now the present-day town of Kętrzyn in the Masurian Lake District of northeastern Poland. Construction completed on June 21, 1941, and Hitler arrived at the base two days later.

Over a period of 3.5 years, Hitler spent around 800 days at Wolfsschanze. More than anywhere else during the war. He left Wolf’s Lair in November 1944, a couple of months before the Red Army seized control of the base.

Wolfsschanze is an interesting historic location, and even if you are not a war history buff, it’s worth visiting if you are in the lake district.

You can visit Wolf’s Lair as a long day trip from Gdansk (280km, 3h drive one-way) or Warsaw (260km, 3h45m drive one-way). While this is doable, I recommend staying a night or two in the Masurian Lake District.

The address to the Wolfsschanze historic site is Gierloz 5, 11-400 Kętrzyn. You can also use the coordinates 54.0805, 21.4943 or the Google Maps plus code ‘3FJV+7P Gierloz’.

The lake district is a popular vacation spot with plenty of options for outdoor activities. Tourists come here for kayaking, mountain biking, fishing and water sports on the lakes. I spent a lovely afternoon kayaking on the Krutynia river.

Wolfsschanze is close to Gierłoż, a village 8km east of Kętrzyn. It’s easiest to visit by car, but if you don’t have your own vehicle, you can take a taxi from Kętrzyn.

The Polish state’s Srokowo Forest District manages the Wolfsschanze historic site. The recently refurbished grounds are well-organized with a big parking, restrooms, a restaurant, ATM and guide services.

Many online reviews of Wolf's Lair complain about mosquitoes. I didn't see any mosquitoes in late July, maybe I was lucky? To be on the safe side, bring mosquito repellent when visiting in summer.

To enter the grounds, you buy a ticket from your car before driving through a gate to arrive at the parking. I saw cars parked at the side of the road outside the premises. Parking there is a bad idea, because the police were busy ticketing the cars when I passed by.

For practical information, see the official website. It’s in Polish, but the translated version works well. Here is some basic information valid during the 2020 season.

The official website isn’t the most easy to find information on, but there are also apps for iOS and Android. The name of the app is Wilczy Szaniec, which is Polish for Wolf’s Lair.

I’ve only tried the iOS version, and most of the information is in English with a few sections in Polish. Some information is only available while using the app onsite, but all the important details can be read anytime.

Wolfsschanze, also spelled Wolfschanze, is derived from Wolf, a self-adopted nickname of Hitler. Wolf was used in several titles of Hitler's headquarters throughout occupied Europe, such as Wolfsschlucht I in Belgium and Werwolf in Ukraine.

— Wikipedia

Wolfsschanze was the largest of the Führer Headquarters, with around 80 buildings and 2000 people stationed at the base in 1944. The grounds consisted of three concentric security zones, Sperrkreis I, II and III. Sperrkreis I contained the bunkers of Hitler and his inner circle.

A perimeter fence guarded by the SS security force Reichssicherheitsdienst (RSD) marked the boundary of the inner security zone.

The Führerbegleitkommando (FBK) managed the personal security of Hitler within the zone. Members of the FBK were the only armed personnel allowed near Hitler.

Hitler, Stauffenberg and Keitel.

Hitler, Stauffenberg and Keitel.

Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0 DE

It was a top secret project to establish Wolfsschanze. Officially, a new chemical plant, Chemische Werke Askania, was under construction. The area of the whole compound was 8 km2, including large forested parts. Barbed wire and minefields protected the 2.5 km2 headquarters area. After the war, it took ten years to clear the area of somewhere around 54.000 land mines.

Wolfsschanze was like a small town, served by airfields and a railway station. The base had power stations, a water supply network, and a heating system. For recreation, there was a teahouse and a cinema.

There are two Kasino buildings, but Wolf’s Lair was not the Las Vegas of East Prussia. The German word kasino means mess, an area where military personnel eat and socialize.

The dense forest protected the headquarters from being discovered by Allied spy planes. To hide the buildings, they used bushes, grass, artificial trees and camouflage nets changed four times a year. Aircrafts photographed the base to ensure it had a sufficient camouflage.

A mix of seagrass, cement and green paint covered the facades of the buildings to make them blend with the surroundings. The coating remains on some structures, like on the heating plant chimney in the photo above.

Wolfsschanze had many kinds of buildings, everything from reinforced bunkers to wooden barracks. Depending on the purpose of a structure, the construction material was wood, masonry or concrete.

For visitors, it’s the heavy bunkers that are the most interesting of the remaining objects. The bunkers were built to withstand heavy bombardments from the Allied forces. Most of the bunkers had limited space inside and were not living quarters, but used as shelters during air attacks.

Blitzkrieg is a term used to describe a method of offensive warfare designed to strike a swift, focused blow at an enemy using mobile, maneuverable forces, including armored tanks and air support.

— history.com

The planned lifetime of Wolfsschanze was shorter than the 3.5 years it lasted before being demolished. The blitzkrieg against the Soviet Union came to a halt when the German army suffered a major defeat outside Moscow in December 1941. Because of the prolonged Soviet campaign, the Wolf’s Lair headquarters was reinforced in 1942.

In 1944, with increasing threats from the approaching eastern front and the extended range of enemy bombers, the major bunkers were further reinforced to withstand a direct hit from the heaviest of the Allied bombs.

The bunkers had 2m thick steel-reinforced concrete walls and ceilings. While that was enough to protect against regular WWII bombs, it was no match for the 10-ton Grand Slam bomb carried by the British Avro Lancaster bomber.

For increased protection, the bunkers were enclosed with an outer shell of reinforced concrete. Between the inner and outer concrete layers, a 0.5m gap filled with basalt grit absorbed the shock waves from bomb strikes.

The outer ceiling layer was at least 3.5m thick and made of fat concrete with dense steel reinforcements. The bunkers rested on a 3-4m thick foundation slab dug into the ground.

In 1944, Wolfsschanze was a mighty bunker complex, but how much of that remains today? After all, the Germans used a considerable amount of dynamite to blow up the base to render it useless for the approaching Soviet army. The military engineers used about eight tons of explosives to demolish a single bunker.

On January 24, 1945, shock waves from massive explosions spread over the area around Wolfsschanze. Heavy concrete blocks flew through the air and the ice cracked in nearby lakes.

Despite the thorough demolition work, the bunkers still stand firm, albeit cracked apart and with ruined interiors. These bunker behemoths are not easily destroyed.

Don’t expect to see how the bunkers looked inside, there is almost nothing left to explore. A few shelters still have some corridors intact, but most interiors are just a mess of blown-up concrete rubble. Anyway, for safety reasons, it’s forbidden to enter the bunkers.

Historians have uncovered at least 42 attempts to assassinate Hitler between 1932 — 1944. The most common methods were bombs and guns fired at close range, but there is at least one case of poisoning.

I didn’t know what to expect when I arrived at Wolf’s Lair, but I didn’t get disappointed. It is a site of ruins, but it’s fascinating to walk around among the bunkers while reflecting on what happened here 80 years ago.

Before heading out into the forest to look at the bunkers, you need to decide whether to hire a guide. I walked around by myself and that was perfectly fine. It’s easy to follow the signposted trail which takes you to the most interesting bunkers and other important buildings.

All major buildings have information panels in English, Polish, German and Russian with facts about the objects. The phone app also has similar information.

In the company of a professional guide you can of course get even more information and a better sense of how life at Wolfsschanze was in the 1940s. Guides are available at the site, and I don’t think it’s necessary to book in advance.

If you want to arrange a guide before arriving at Wolf’s Lair, the official website has a list of guides giving foreign language tours.

The Wolf’s Lair historic site covers a large area, but it’s easy to find your way around. Next to the parking is a large light blue building. The building, now converted to a hotel, is the former residential quarters of the Reich security service Reichssicherheitsdienst.

There is also a restaurant, restrooms and an ATM here. This location was within the bounds of Sperrkreis III, the outer of Wolfsschanze’s three security zones.

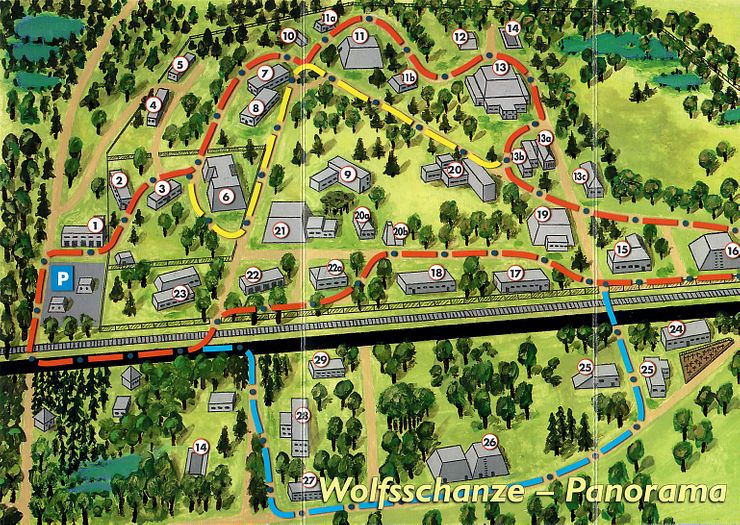

On the walk from the hotel to the bunker area, you pass by a gift shop where they sell souvenirs and Wolf’s Lair publications. I bought the Wolfsschanze tourist guide, a booklet with historic information and a map with the bunkers and suggested walking trails.

You can wander around and look at the bunkers in any order you want, but it’s easiest to follow one of the signposted trails through the forest.

The map in the tourist guide booklet is not updated with the recent additions to the site, but it contains all the bunkers. Most visitors follow the red trail passing by the most interesting bunkers and buildings.

It’s an easy stroll on a paved walking path through flat terrain. Allow 1—3 hours for the tour depending on how many of the bunkers you include.

The highlights are the General purpose bunker (11) used by Bormann, Hitler’s bunker (13) and Göring’s bunker (16).

One of the first buildings on the red trail is the Lagebaracke (3), where the assassination attempt on Hitler occurred in 1944. Here you will have to use your imagination because the concrete foundation is the only remaining part of the building.

Later on you will arrive to a barrack building housing an interesting exhibition covering the assassination attempt.

Continuing on the path, you will soon arrive at building number 6, the huge guest bunker. The shelter had 7m thick walls, and it was one of the most important buildings in Zone I. Hitler’s guests stayed here when visiting Wolf’s Lair.

Hitler used the bunker himself for four months in 1944, while his new bunker was under construction. Despite its size, 45m long and 23m wide, the guest bunker had only two rooms.

The brick and concrete barrack labeled number 7 was the workplace for stenographers transferred from the German parliament to the Wolf’s Lair. They made records of important meetings such as the sessions involving Hitler and the senior military command.

The general purpose bunker (11), also known as Bormann’s bunker, was a heavy air-raid shelter for protection during air attacks. The living quarters of Martin Bormann were next to the bunker.

Bormann was Hitler’s private secretary and head of the Nazi Party Chancellery. As a member of Hitler’s inner circle, he was one of the most powerful persons in Nazi Germany.

The Führer bunker (13) from 1944 is the largest shelter in Wolfsschanze. Measuring 67m x 38m, it’s a colossus of concrete and steel. Hitler lived in the bunker for a mere twelve days between November 8—20, 1944 before relocating to Berlin.

The bunker replaced a smaller shelter built in 1941 and upgraded in 1942. The 8.5m thick roof protected the interior comprising a bedroom, a bathroom, and an office. An information panel outside the bunker displays a photo of the office.

Concrete extensions on the flanks contained a kitchen, a dining room and a chamber for staff briefings. Nothing of the interiors in the bunker or the flanks remain today, it’s all rubble. The anti-aircraft tower mounted on the bunker roof, now lies on the ground behind the building.

On the photo below is one of several entrances to Hitler’s bunker. The metal doors had rubber seals to protect against gas attacks.

The bunker looks almost intact from the outside except for the cracked walls. Considering the size of the fissure in the middle of the bunker, the power of the explosives used to blow up the interior must have been enormous.

Hermann Göring, commander in chief of the Luftwaffe and founder of the Gestapo, had both a house and a bunker in Wolfsschanze. Ironically, he didn’t stay even a single night at the base.

Göring’s bunker (16) is maybe the most interesting building at Wolf’s Lair because some interiors survived the demolition charges. That’s quite remarkable because the explosion had enough power to lift the massive bunker roof.

The bunker measured 27m x 21m, and it had multiple anti-aircraft guns and an MG-42 machine gun on the roof. A corridor ran through the bunker that had two rooms and an internal metal clamp ladder leading to the roof.

It’s forbidden to enter the bunker because of the risk of collapse, but I saw several curious visitors taking quick looks inside.

Both the Göring buildings are at the far end of the site. I didn’t pay attention and made a wrong turn, so I had to walk back when I realized I had passed the buildings already.

Object number 19 doesn’t stand out among the bunker ruins, but it was the shelter of Wilhelm Keitel, another member of Hitler’s inner circle.

Keitel, Chief of the Wehrmacht, was known as Hitler’s yes-man. Hermann Göring described Keitel as having “a sergeant’s mind inside a field marshal’s body”.

I didn’t walk the trail marked with blue on the map, but there is one interesting object on that path. The Wermacht bunker (26) was a huge air-raid shelter, only Hitler’s bunker was larger. Steel clamps attached to the concrete front wall provided access to the gun stations on the roof.

In 1944, a growing number of military leaders disagreed with Hitler’s strategic decisions. The war was not going well, Germany was on the road to disaster. A group of high-ranking officers plotted to kill Hitler and activate Operation Valkyrie.

Hitler had approved Operation Valkyrie, a plan to be implemented should the Reich be in imminent danger. The plan defined how to deal with internal disturbances and maintain civil order in the country by deploying the reserve army.

In secret, the conspirators made several modifications to the original version of the plan. They intended to seize power in Berlin and execute key members of the Nazi leadership.

Following the establishment of a new government, negotiations to end the war would start. The goal was to agree on surrender terms favorable for Germany. The news about Hitler’s death was going to be the first in a chain of events leading to a successful coup d’état.

The key conspirators were General Friedrich Olbricht, Major General Henning von Tresckow, and Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg. They convinced Friedrich Fromm, Chief of the Reserve Army, to participate in the coup. It was only Fromm and Hitler himself who could initiate Operation Valkyrie.

Claus von Stauffenberg was a German aristocrat and Wehrmacht officer. During service in North Africa, he sustained severe injuries and lost an eye, his right hand, and two fingers on the left hand. Stauffenberg sympathized with German nationalists, but he disliked the methods of Hitler and the Nazi party.

Claus von Stauffenberg (Wikipedia, license).

Claus von Stauffenberg (Wikipedia, license).

On July 1, 1944, Stauffenberg was appointed Chief of Staff of the Reserve Army, a position which gave him access to Hitler. On the morning of July 20, Stauffenberg traveled to Wolf’s Lair to attend one of the regular strategy meetings with Hitler and the military command.

Together with his aide Werner von Haeften, Stauffenberg arrived at the Wolf’s Lair airfield around 10:15. He had prepared two time bombs, each made of a 1kg explosive charge with a pencil detonator.

Stauffenberg met with onsite coconspirator General Fellgiebel, responsible for cutting the communications from Wolf’s Lair to the outside world after the death of Hitler. So far, everything went according to plan.

With all preparations set, Stauffenberg reported to Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. Now things started to go wrong.

The strategy meetings were usually held in a windowless bunker where a bomb would do massive damage to persons inside it. It was a hot day, and the meeting had been moved to a nearby wooden barrack, the Lagebaracke. The windows were open to let the air flow through the conference room.

Hitler's torn trousers.

Hitler's torn trousers.

Wikimedia Commons/CC BY-SA 3.0 DE

Keitel informed Stauffenberg that Hitler had brought the meeting forward to finish in time for welcoming Benito Mussolini, expected to arrive at Wolf’s Lair later in the day.

Stauffenberg realized he would not have time to arm both bombs. One explosive charge risked being too weak to take out Hitler, but he had to push forward.

He made an excuse to wash up in Keitel’s quarters, where he used pliers to crush a section of the pencil detonator to start the countdown. Stauffenberg now had around ten minutes before the bomb would explode.

A recent addition to the Wolfsschanze historical site is an exhibition about the assassination attempt. It’s on display in a building where they have recreated the meeting room in which the attack on Hitler occurred.

Keitel and Stauffenberg entered the conference room sometime after 12:30. The meeting was underway and after a few minutes, Stauffenberg excused himself, saying he had to take an important phone call. Before leaving the room, he placed his briefcase with the bomb under the conference table near Hitler.

At 12:42, the bomb detonated. The cavities between the floor-boards and the open windows absorbed much of the energy of the blast. Hitler escaped death because he was leaning over the table inspecting the strategy maps. The sturdy table shielded him from the full power of the explosion. Hitler sustained light burns, bruises, and a perforated eardrum.

Of the 24 persons present in the room, the bomb mortally wounded four, and the rest received minor injuries. Stauffenberg assumed that Hitler had died and left Wolf’s Lair with a plane back to Berlin.

Based on the incorrect information that Hitler was dead, the conspirators in Berlin initiated Operation Valkyrie. The coup attempt didn’t last long, news soon arrived that Hitler had survived. Himmler issued orders countering the mobilization of Operation Valkyrie.

In an attempt to save himself, General Fromm turned on his fellow conspirators. He arrested and executed Olbricht, Stauffenberg and von Haeften. Henning von Tresckow committed suicide when realizing the coup had failed.

In the following weeks, the Gestapo performed a thorough investigation, making over 7000 arrests and executing almost 5000 persons.

Field Marshal Erwin Rommel didn’t have an active role in the plot, but he supported the conspiracy. Being a national hero, Hitler gave him the choice of being executed or to commit suicide. Rommel selected to take his own life.

Kętrzyn is not on the common tourist route through Poland for international visitors. It’s location in the northeastern corner of the country is a bit off, but the area is a prime domestic tourist destination.

The Great Masurian Lakes, a series of lakes connected by rivers and canals, attracts people to the region during the summer months. The extensive system of waterways is perfect for canoeing and kayaking.

What might be the best kayaking trail in Poland runs on the Krutynia river. It is a 100km multi-day trip for kayaking enthusiasts. You can get a taste of the river on a half-day kayak outing if you are in the lake district for only a day or two.

The most popular section of the river is the 13km between the towns of Krutyń and Ukta. It is 3-4 hours of paddling on the shallow and very calm river with crystal clear water.

The route is easy and suitable for families with children and people with no experience of kayaking or canoeing. I had a great time on the river and I can recommend this activity if you want to try some easy kayaking. See my post on Kayaking on the Krutynia river for more information.

If you are driving between Warsaw and the Wolf’s Lair, I recommend making the 1h detour to visit the Treblinka memorial site.

Treblinka was a Nazi extermination and labor camp in use between 1941-1944. An estimated 800,000 jews died in Treblinka, more than in any other extermination camp except Auschwitz-Birkenau.

The Nazis shut down the extermination camp (Treblinka II) in 1943 and the labor camp (Treblinka I) in 1944. Almost nothing remains of the camps, but there is a small museum and memorial at the site that was declared a national monument of Jewish martyrdom in 1964.

While researching the historic material for this post, I stumbled upon on a paper titled Material and Construction Solutions of War Shelters with the Example of Hitler’s Main Headquarters in the Wolf’s Lair. If you are interested in learning about concrete mixtures and shelter construction principles, check out the PDF. It’s actually quite interesting!

Comments

Comments are closed. Contact me if you have a question concerning the content of this page.