Gliwice radio tower

November 15, 2019 8 min read

The radio tower in the Polish city of Gliwice is both a striking landmark and a building of historical importance. Gliwice is about 25km west of Katowice in the Upper Silesia region in southern Poland.

The tower is part of a broadcasting facility also including a radio station museum. While the site isn’t one you would plan your itinerary around unless you are into war history or transmission towers, it’s still worth a visit if you are passing by Gliwice on your road trip through Poland.

The transmission tower is remarkable because it’s the tallest wooden structure in the world. The radio station played a part in the events preceding the start of World War II when the Germans staged a false flag operation at the station to justify the invasion of Poland in 1939.

Back in 1935 when radio transmissions from the tower started, the region was German territory. Gleiwitz is the German name for Gliwice and the official name of the tower was Sendeturm Gleiwitz. Locals called it the Silesian Eiffel Tower because of the resemblance to another more famous tower.

The tower is built of impregnated larch wood and it’s the only remaining pre-war wooden radio tower. More than 16.000 brass bolts join the beams together. The wooden construction is 111m (364ft) tall and the tower is 118m (387ft) including the antenna on the top. When illuminated by eight large reflectors at night, the tower is visible from several kilometers away.

The German radio used the tower for medium wave transmission. After World War II, the tower remained in service for the Polish radio until 1955. The Soviets then took charge of the facility and used it to jam Western Europe radio stations broadcasting programs in Polish.

The tower is still in use today, both for mobile phone services and low-power FM transmissions.

This post contains its fair share of historic information. The radio tower is an impressing piece of engineering, but the pre-war history of the site is what makes a visit here really interesting.

The sources I’ve used to collect the information differ on some facts, it’s difficult to know what happened at the radio station the day before the war started. I’ve tried to summarize the events to the best of my ability.

In August 1939, Hitler had already decided to invade Poland, but he wanted something to use as an excuse for the aggression. For some time, Germany had conducted a propaganda campaign accusing Poland for ethnic cleansing of Germans living in Poland. Furthermore, they planned and executed a series of false flag operations just before the start of the war. The Nazis faked Polish attacks on German targets.

A political or military action that is made to appear to have been carried out by a group that is not actually responsible. -- Cambridge Dictionary

The campaign was named Operation Himmler after Heinrich Himmler, the leader of the Schutzstaffel (SS). Reinhard Heydrich, head of the SS intelligence agency Sicherheitsdienst (SD), and Heinrich Müller, chief of the Gestapo, were in charge of the operation.

The Gleiwitz incident was the most important of the missions planned for Operation Himmler. The team selected for the mission was a Special Operations Task Force (Einsatzgruppe) under the command of SS officer Alfred Naujocks.

Naujocks is the major source of information of what happened at the radio station. He turned himself over to the Americans in 1944 and his affidavit from the Nuremberg Trials covers most of what we know about the Gleiwitz incident.

The goal of the mission was to stage a Polish attack on the radio station in Gleiwitz. A propaganda message in Polish sent from the station should give the impression of a Polish assault on Germany. To give credibility to the action, there had to be a fatal casualty among the attackers proving Polish involvement.

Naujocks and his team of five or six men arrived in Gleiwitz some two weeks before the attack on the radio station. Disguised as Poles, they stayed at the Oberschlesischer Hotel, ready to take action when the order arrived.

Naujocks stated that “At noon on the 31st of August I received by telephone from Heydrich the code word for the attack which was to take place at 8 o’clock that evening”. The code word, and likewise the name of the mission, was Grossmutter gestorben (Grandmother died).

The team prepared for the attack by dressing as Polish rebels. They needed a body to set the scene at the station to look like a rebel was killed during the attack. Naujocks arranged with Heinrich Müller to get a body delivered to Gleiwitz.

The unfortunate victim chosen by Müller was Franciszek Honiok, an ethnic Pole living in a village close to Gleiwitz. SS arrested Honiok the day before the attack and selected him because of earlier involvement in local revolts against German rule in Silesia.

In his affidavit, Naujocks stated that Müller had 12 or 13 convicted criminals that similar to Honiok were potential fatal casualties during Operation Himmler. Müller referred to them as Konserve (Canned goods). Honiok was still alive when taken to the radio station, but he was unconscious after being drugged.

The attackers didn’t meet any resistance; they captured the staff on duty that night and tied them up. Then the problems started.

"We seized the radio station as ordered, broadcast a speech of 3 to 4 minutes over an emergency transmitter, fired some pistol shots, and left." -- Alfred Naujocks

What Naujocks didn’t know beforehand was that the Gleiwitz station only worked as a relay transmitter, not as a broadcast station. The tower relayed broadcasts from Radio Breslau (today Wrocław) located around 150km from Gleiwitz. There was no proper broadcasting equipment at the station.

Facing the risk of a failed mission, Naujocks and his men found an emergency transmitter equipped with a microphone. The transmitter had limited power; the city used it in case of extreme weather to warn people living in the area.

Using the emergency transmitter, a Polish speaking member of the team broadcasted a message. The full message was several minutes long, but with the equipment problems, they could transmit only a fraction. Radio listeners in Gleiwitz and surrounding towns heard a short confusing message in Polish.

Attention! This is Gliwice. The radio station is in Polish hands...

After finishing the transmission, the attackers fired some shots, killed the unconscious Honiok and left his body outside the building. In a way, Honiok was the first casualty of World War II.

German radio reported about the “Polish” attack the same evening. Foreign media also mentioned the incident, BBC the same evening and New York Times on the following day.

Fall Weiss (Case White) was the Nazi strategic plan for invading Poland. On the 1st of September 1939, the day after the Gleiwitz incident, Hitler initiated the plan and started the Second World War by attacking Poland. In his declaration of war, Hitler didn’t mention the Gleiwitz incident specifically, but referred to the series of faked provocations as a Polish assault on Germany.

If you are heading towards Gdańsk, you can follow up the visit in Gliwice with a tour of the Westerplatte peninsula in the Bay of Gdańsk. German army, naval and air forces fired the first shots of the war while attacking a Polish military installation at Westerplatte. The famous battleship Schleswig-Holstein participated in the attack.

The A1 and A4 highways pass by the city which is 30km west of Katowice, 110km northwest of Kraków and 165km southeast of Wrocław (driving distances). Coordinates 50.3133, 18.6888 and Google maps plus code 8M7Q+8H Gliwice, Poland. Google maps has a nice 3D view of the tower and the surrounding area.

Entering the facility through the main entrance from the Tarnogórska road, the old radio station, now a museum, is straight ahead. The radio tower stands in a park behind the museum building. There is a parking on the Lubliniecka road behind the radio tower so if you are arriving with a car it’s easiest to enter the park from that side.

I recommend visiting the museum when you come here to see the tower. The museum website doesn’t have much information, but it lists the opening hours. The door to the museum building was locked when I visited and I thought the museum was closed. I don’t remember if there was a door bell or if I knocked on the door, but after a little while the staff came to open so I could enter.

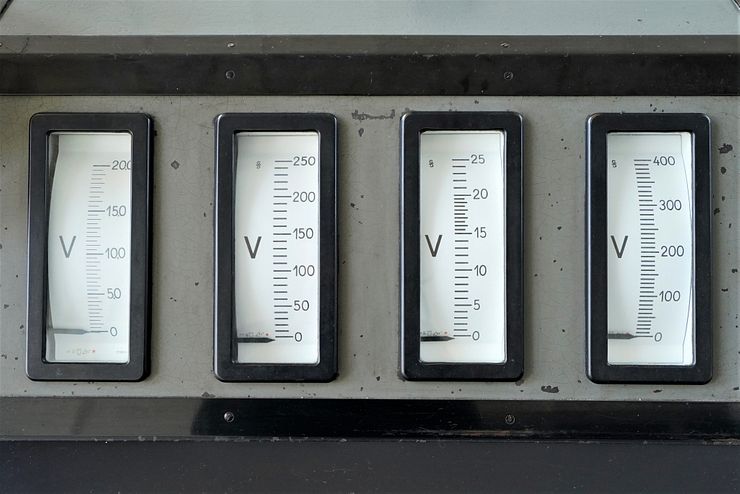

The museum is small, and it doesn’t take much time to look around in the main room containing old radio transmission equipment. I love these old oversized devices equipped with gauges, control switches, levers and metal wheels.

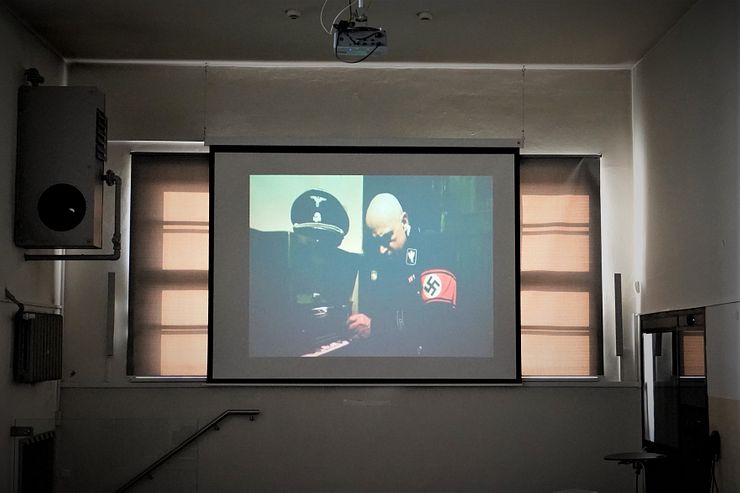

A film about the Gleiwitz incident is shown in another room. I was the only visitor at the museum, and the kind staff prepared the film while I was looking at the exhibition. The film is well made, allow 20–30 minutes for watching it and learn about the history of the radio station.

If you are interested in reading Naujocks’ own words, excerpts from the Nuremberg trials affidavit are available here (scroll down to page 242).

Comments

Comments are closed. Contact me if you have a question concerning the content of this page.